Through the Looking Glass: BFI's 'The Creative Worlds of Powell + Pressburger'

J Taylor-Jones was invited to step into the worlds of Powell & Pressburger via the BFI's comprehensive season of screenings, talks and art. This what they thought...

As a young British programmer and filmmaker, I have heard and seen two names that rear their heads out of the mists of conversation so often, together a cornerstone of our cinematic culture that, from the point of its emergence, has left its mark on more work that can possibly be comprehended. Those names, of course, are Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

Until not so long ago, I am somewhat ashamed to admit, I had never seen a work from the filmmaking duo. I had heard so much, but I hadn’t had the privilege of seeing any one of their films. With my desire to dive into the Powell & Pressburger filmography so great, but having no real access to it, I was delighted when it was announced that the British Film Institute would be curating a multi-platform, all-encompassing season of their work, Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell + Pressburger, and that their most popular releases would receive re-releases in cinemas nationwide. Finally, these stalwarts of British cinema were being introduced to a new generation - including me! In early October, my path to Powell & Pressburger officially started when the BFI reached out to me and asked me to step through the looking glass and attend some of their events in the season - how could I refuse?

In the latter half of October, I made my way up to the less-than-sunny Southbank to visit the National Film Theatre, very excited to have been invited to see Thelma Schoonmaker in conversation - the main topic being the works of Powell and Pressburger through her very personal connection to them, Schoonmaker herself having been the late Michael Powell’s wife. Of course, it is undeniable that Schoonmaker is known better - by my generation, at least - as the editor and magician behind the films of the Martin Scorsese, which, to me, was a great bridge between a filmography whose cultural significance I am very familiar with and another whose significance I had unconsciously observed but never fully engaged with. I arrived at Southbank and was glad to find shelter from the biting cold upon entering the National Film Theatre itself, where I was promptly guided past the ever-growing queue for standby tickets to register my arrival. I soaked in the atmosphere of the building for maybe ten minutes more, attempting not to empty my entire life-savings in the shop before making my way to the capital city of film screens, NFT1.

As the lights dimmed and the audience hushed, the tension grew as we were introduced to the Cinema Unbound season, all of us collectively anticipating the arrival of the woman of the hour. I had observed, though, in my naturally curious/nosy fashion that upon entering the room, most other audience members were recounting to each other stories about Powell & Pressburger films. I struggle to recall any particular stories, but there was a sense that these were holy grails, jewels in the crowns of memory and mile-markers in individual paths of life, and everybody in the room was more than keen to hear them talked about on stage; it didn’t seem to matter who was talking about them, the fact that it was going to be a globally celebrated filmmaker was insignificant next to the sacred subject of the conversation. Soon enough, Thelma took to the stage in humble fashion, and mere seconds after she sat down the anecdotes and discussion started - she may have been the most excited person in the room to speak about Powell & Pressburger - and we all sat watching like hungry dogs scrounging for food.

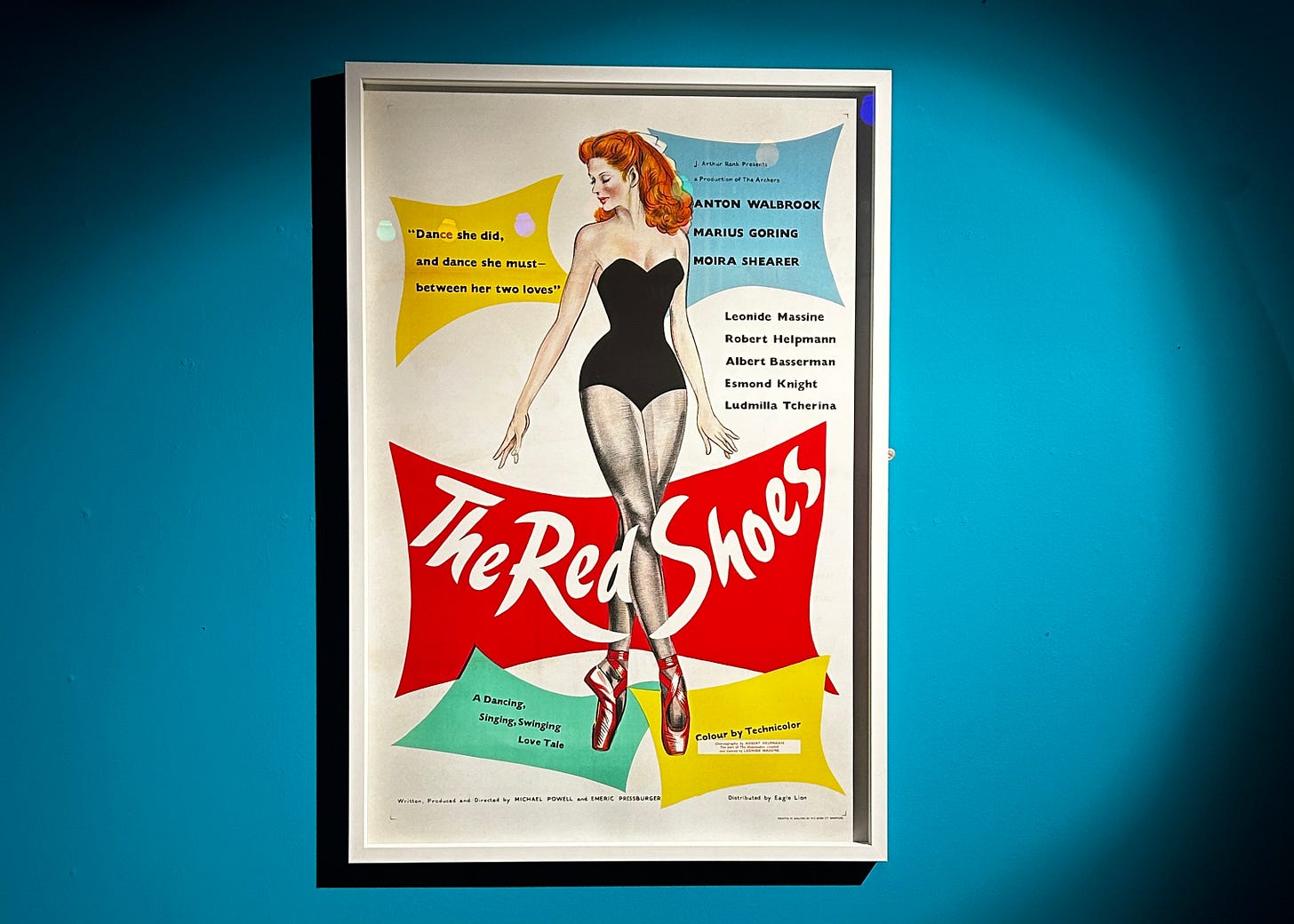

It’s hard to write about an event that was just someone talking - with very interesting things to say, no less - without just repeating what was said, and, honestly, I don’t think that would be of much, if any interest. There wasn’t any one thing in particular that Schoonmaker spoke about that summed the evening up, instead it was the vitality that the films breathed into her. The event was punctuated with numerous clips from Powell & Pressburger films, most notably The Red Shoes, Gone to Earth and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, and each seemed to give Schoonmaker a boost after her oft-moved exclamations of “beautiful…” that followed every clip. The clockwork nature of this would be quite funny in other situations, but she was completely right. Even with little context, these clips - my very first taste of this filmography - struck me in such a strange way. The beauty with which landscapes were shot, the subtle emotions that took hold of me with such power, the larger-than-life nature of the abandonment of reality; everything was so fresh, even roughly eighty years after some of these films were coming out (and even in truncated form) they felt so deeply original, both visually and inwardly. Though I doubt I would have felt much differently without them, Schoonmaker’s contextualisation of Powell & Pressburger’s films, and particularly Michael Powell’s life, made for the ideal initial exposure, like opening a can of golden worms with a softly-spoken guide who tells you where they came from and exactly what the can is made of. The evening was full of wonderful personal anecdotes that only added to my eventual dive into the sea of Powell & Pressburger, though instead of hitting the water and being overwhelmed by it, when I later landed in my seat for The Red Shoes, I had some kind of idea about the marvel I was about to subject myself to.

As I mentioned earlier, it’s hard to move in British film circles without encountering Powell & Pressburger’s films, or their fans. When I was invited to see The Red Shoes - also in NFT1 - I was quick to share this with my immediate film family. I had told my housemate that I would be seeing the famed dance film and she looked at me as if she were a child who had just learned she would be going to Disneyland (and she wasn’t even seeing the film!) I can’t quite remember exactly how she put it to me, but she told me quite quickly that it was one of the most important films to her and amongst her favourites ever. In retrospect, this makes complete sense; not only does it fit my housemate like a glove, but it is, and was, unlike any other film I’ve seen on the big screen.

A couple of weeks after giving audience to Thelma, with ample time to excitedly await my colourful introduction to the creative worlds of Powell & Pressburger, I made my way back up to the National Film Theatre and to my seat, where I sat down in my usual anxiously early fashion. Coincidentally for a screen that then had maybe five other people in it, my seat just happened to be next to one already occupied. Waiting for the film, I got talking to my seat-neighbour, once again about the legendary status of Powell & Pressburger, particularly about The Red Shoes, and about how she saw the film once before on her television as a child. What fascinated me was how, almost like my housemate, she spoke of the film as if seeing it was akin to a religious experience; she described to me numerous sequences in great detail, clearly ingrained deep into her memory, colours still burned bright into her eyes. It was a great appetiser, to say the least, so as the film began I tried to suppress a giddy excitement that had been planted deep in my cinephilic soul - perhaps over several years. Even in its opening credits and first scene, there was a tangible sense of wonder that rose up inside of me. It might have had something to do with the anticipation I had been feeling all day, but equally I felt so engaged with what was happening, like the directors were themselves on stage performing magic tricks with flashpaper and magic hats.

As a filmmaker, I tend to watch films with a sense of detachment from the experience that I imagine the average filmgoer would forgo. It’s my craft, I understand the processes that go into telling these stories, so I see those techniques being used and understand them. Considering this and realising that I forgot what I was watching was a film in the time-shifting moment that the credits start to roll, I developed such a strong admiration for it, and The Red Shoes managed to place me within that perfect space in its first ten minutes. I was one of those excited theatregoers, hanging onto every word and every shot with infinite anticipation for the next. The colour, the costumes, the dynamics, the dance, the music, the dialogue, it all married together like a bespoke magic carpet, sweeping me up and leaving me floating in a strange warm filmic haze. It’s a universal story of course, perhaps made universal by this film, but the turmoil of Moira Shearer’s Victoria Page as she chooses between love and art still proves as compelling and stunningly beautiful as ever, still lending us characters and situations whose influence is felt in films as popular as The Souvenir (parts I & II), An American In Paris and The Shape of Water, as well as the wider works of Damien Chazelle, Wes Anderson and even Martin Scorsese - and yet it still holds up as the best of its kind. It’s an enigmatic and charismatic work of wonder whose light shines in every corner of the modern cinematic landscape - and continues to inspire and enlighten.

It’s easy to see why its first audiences, who were undoubtedly still feeling the effects of World War II, as British streets were reconstructed and families still processed the loss of loved ones, were so taken by The Red Shoes, so caught up in its infectious vibrancy. It’s quite apt that we’re seeing the rerelease of the film now, in a time rife with conflict, prejudice and poverty. The Red Shoes is the type of film that fills one with pure joy, a suspension of the negativity outside of the four borders of its frame that allows its viewers to glue themselves to the troubles and, more significantly, the exuberance of its characters, removing for just two hours whatever ails them. Perhaps this is true of all cinema, but for the cinema of Powell & Pressburger, as I am so readily discovering since seeing Peeping Tom at Brighton’s 21st Cinecity Film Festival and A Matter of Life and Death in the comfort of my own home, but especially true of The Red Shoes, is that every frame that Powell & Pressburger committed to celluloid was done so with a passion that bleeds from the scenes they make up, along with unparalleled love, hope, terror, pain and curiosity. In other words, they were - and still are - in possession of some strange essence that has everyone turning to hear their words and see their sights. They are their own genre of cinema and I’m beyond glad to have been given such a fine opportunity to introduce myself to their work with Cinema Unbound.