Reflecting on Goodbye, Dragon Inn and the Cycle of Cinemagoing

Louise reminisces on our previous screening, 'Goodbye, Dragon Inn', and the types of cinema in which it is set and was shown.

A few Wednesdays ago we had the pure joy of screening Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Tsai Ming-liang, 2003) at Depot Cinema.

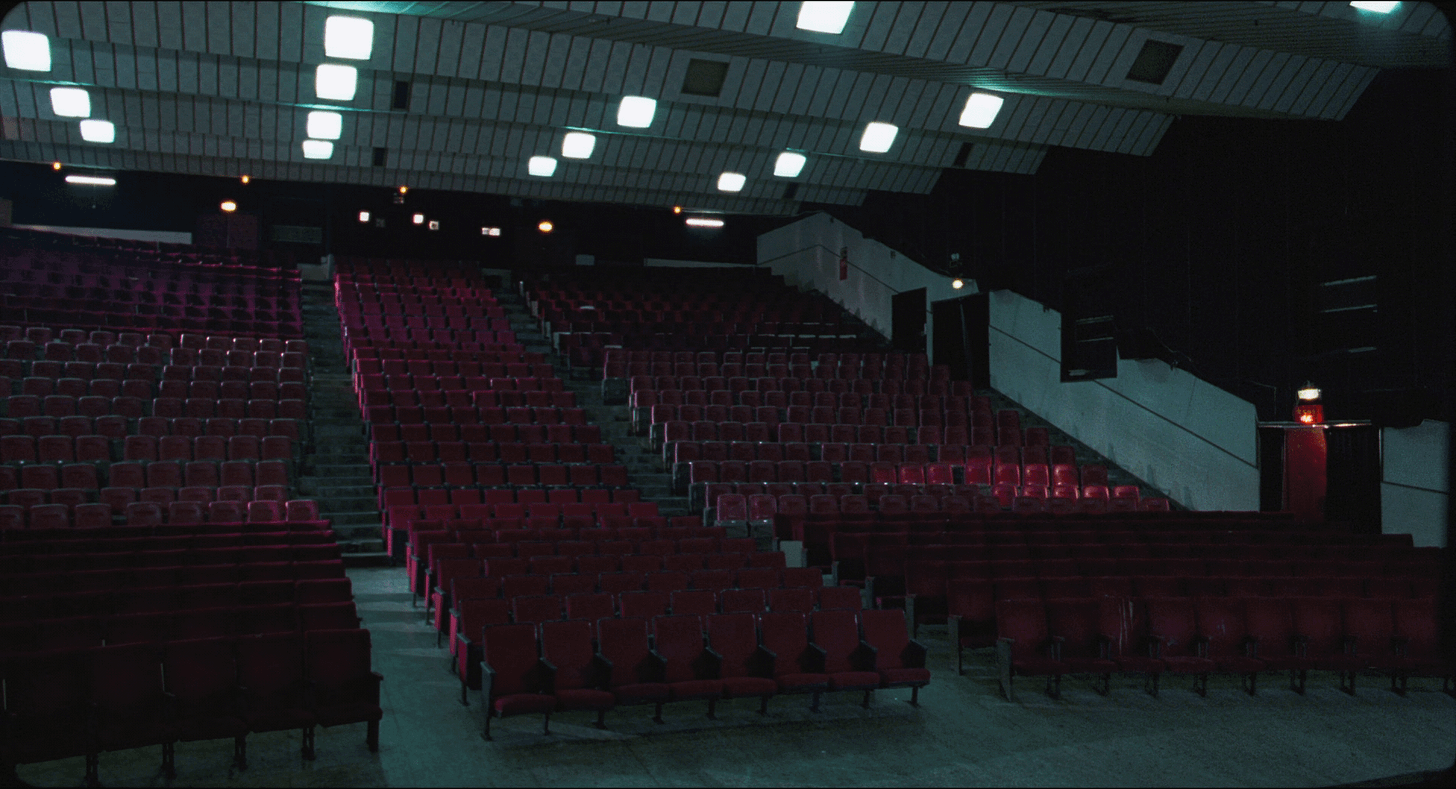

The Fu-Ho cinema in which Goodbye, Dragon Inn is filmed couldn’t be more different to Depot. Built in 1972, the Fu-Ho was a single screen 1,000 seat cinema in Taipei, Taiwan, playing second-run double-bills, whereas the Depot is a completely digital, 3-screen cinema that opened in 2017. Yet, when the rows of seats on screen line up with those in the auditorium, the universal experience of cinema could not be more poignantly encapsulated.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn’s original title 不散 translates literally to “no leaving” – an arguably more fitting title to a film about cinemas haunting ability to preserve a space full of past shared experiences and memories. The cinema holds space for potential, a potential which lingers way after the audience has left, even for good. Tsai Ming-liang saw this when he set a scene of his prior film What Time Is It There? (2001) and packed out the cinema for a screening of the film. This success led to the cinema’s owner trying to convince Tsai to run the about-to-close cinema. Instead, Tsai proposed that he rent the cinema, and he’ll make a film there. What intended to be a short, became Goodbye, Dragon Inn with Tsai later saying “the memories of that cinema became the memories of cinema”.

It’s not a unique experience, just another underpopulated declining cinema. We move on and what’s left behind is reminiscent of the earliest ways in which films were shown – at fairgrounds and traveling shows, anywhere a screen could be set up, a space darkened and a crowd easy to find. Only a patch of dead grass and muddy fields where a travelling show once stood, now empty, derelict cinemas large, imposing spaces of emptiness.

Tracing back the history of cinemagoing, the first permanent theatre devoted exclusively to the presentation of films wouldn’t come till 1905, with the Nickelodeon (10 years after what is generally agreed to be the birth of cinema). Usually converted from a converted shopfront, these small, humble theatres charged a low amount and saw consistent audiences. Nickelodeons were hugely successful, quickly popping up all over the country. They thrived for about 10 years, but as film itself (the format, style, technology and industry) was changing, so did the exhibition space.

Cinemas become more and more elaborate, evolving into “movie palaces” from 1910s, peaking in the 20s and continuing till the 40s. 1920s-30s. Impressive architectural feats with huge capacities, lavish interiors and opulence.

We are lucky enough to have Duke of York’s ‘the oldest purpose-built cinema in the UK that has remained in continuous operation’ close by. Opening in 1910, Duke of York’s

was the vision of actress Violet Melnotte Wyatt. With 800-900 seats when it first opened, changing with sound, technicolour, bigger screens, more leg room (now a capacity of 300) and of course its fair share of bingo nights to remain open across the 60s.

Built like places of worship for cinephiles, filmmakers have often tried to capture this magic on screen for themselves, through arguably none as successfully as Tsai. Sam Mendes attempted to recapture the ‘movie palace’ experience with his 2022 film Empire of Light. Transforming the empty Dreamland Cinema in Margate into the Empire Cinema for the movie. The grand art-deco ‘super-cinema’ had a 2200 capacity when it opened in 1935. Eventually minimising seating in favour of multiple screens, and then succumbing to the popularity of bingo before closing in 2007. Only to be reopened as a filmset. There’s clearly a draw to these buildings, their imposing grandeur as a symbol of the status of cinema.

Built in 1972, the Fu-Ho was large, but not a “movie palace’ in its ornateness - a 1,000-seat cinema as part of a complex, by the time Tsai Ming-liang came to film Goodbye, Dragon Inn, the cinema was already in its final attempts at survival as a porn theatre.

Television would have the biggest impact of cinema-going, followed by the rise of the multiplex and the multi-screen cinema signalling the obsolescence of single-screen cinemas.

There’s something tragically lost in the single screen cinema’s with 1,000+ seats of a cinema-going-time gone by. There’s something undeniably haunting about such a static, empty space, poised for a flicker of light to break the darkness and turn the empty vessel into a magical show ground once again.