Into The Unknown: Five Alternative Horror Films

The Cinelogue team offer five lesser-known horror gems to shake up your spooky viewing this Halloween.

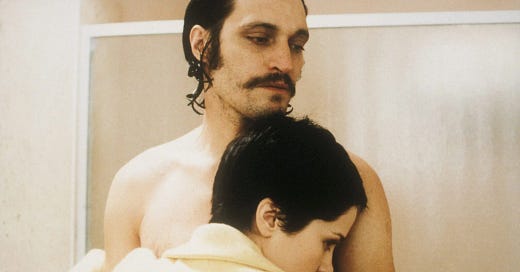

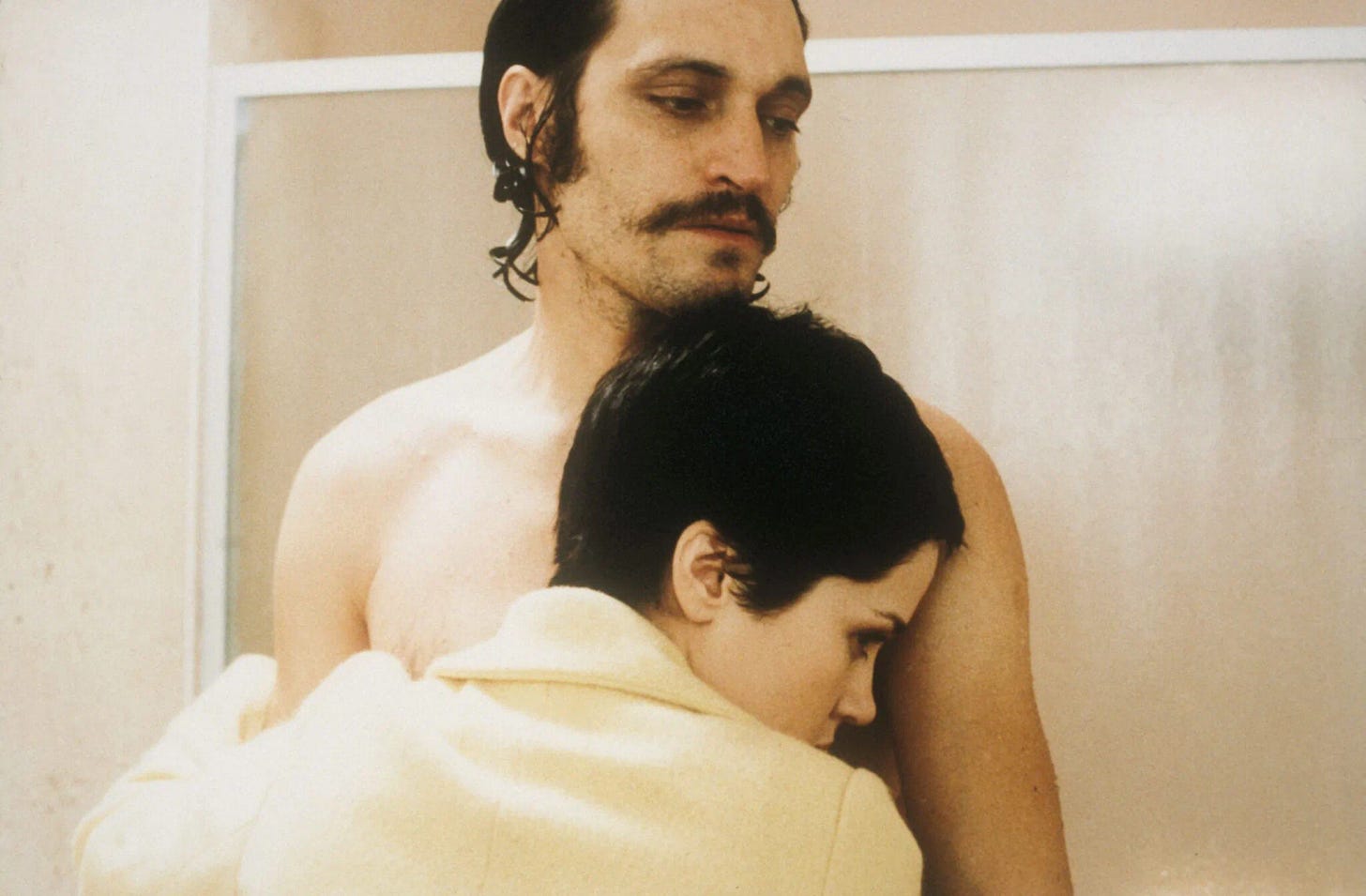

Trouble Every Day (2001) dir. Claire Denis

Post Chocolat and Beau Travail, it’s fairly safe to say nobody expected Claire Denis to treat audiences to a dabbling in the horror genre, though, in retrospect, Trouble Every Day seems like such a logical outcome of her signature interests - the relationship between mentality and physicality. Visceral to such extremes that it rivals even The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Trouble Every Day is an all-bearing examination of sexuality and desire, expressed via vampirism.

As an American plagued by rampant desire lands with his wife in Paris, elsewhere in the city a neuroscientist locks his wife away following her cannibalistic attack on a man at the side of a road in the dead of night. Paths cross and revelations are made about the connections between the four leads, but in the eye of the bloody storm lies a deeply complex discussion of the oppression of female sexuality in a patriarchal society. Like a classic Denis, two lines run parallel; the mind, which is teeming with lust and desire which creates a fascinating - and scathing - story, and the body, which gives way for some of the most disturbing cinematic moments in 21st century horror.

This is one for those bored with mainstream horror, for those who want a slow-burn chiller that steadily evolves into a sickening symphony of screams and sinews. One that also maintains class, dignity and a steely coldness. - J

The White Reindeer (1952) dir. Erik Blomberg

Set among the snow-capped fells of Lapland, The White Reindeer is truly a hidden jewel in both folk horror and Scandinavian cinema. In his visionary directorial debut, Erik Blomberg weaves a gothic fairytale from a young woman’s loneliness and sexual frustration in an isolated mountain village. When the newlywed Pirita’s husband goes away on a work assignment, her feelings of abandonment drive her to procure a love potion from a local shaman, making her the most desirable woman in her community – albeit with deadly consequences.

With its fantastical elements, allusions to witchcraft and therianthropy, and implicitly feminist themes of domesticity and female sexuality, The White Reindeer is in many ways reminiscent of an Angela Carter tale (although a precursor). Combining dreamlike cinematography with strange, monochromatic landscapes and stark framing – often capturing Pirita or mountain wildlife alone in shot – Blomberg conjures a cinema of yearning; one that feels unusually tender for horror, as if we are being lulled into a deathlike slumber amidst the pines and fading Northern Lights. The isolated, hermetic quality of the film itself is also perhaps partly down to the fact that Blomberg served as the writer, director, cinematographer and editor, leading to an artistic vision that is both thorough and highly contained. I’d recommend watching this film going into winter; it’s a cold movie, but one with a surprising and unexpected warmth at its heart. - Imogen

Ghostwatch (1992) dir. Lesley Manning

Is Ghostwatch a film? Even a television film? Let’s settle for ‘Cultural Phenomena’ akin to Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds radio broadcast of 1938. On the night of its broadcast, Halloween 1992, Ghostwatch allegedly caused 1,000,000 calls to the BBC switchboard, comprising a mixture of outrage, baffled concern and acclaim for its originality.

A mockumentary of sorts, Ghostwatch was a ‘live’ investigation of the spectral activity at 41 Foxhill Drive. The legendary Sir Michael Parkinson presents from a BBC studio with Craig Charles and Sarah Greene live on the scene, Greene’s husband Mike Smith mans the studio telephone switchboard. The result is a bit like Comic Relief but for conspiracy theorists.

Shenanigans ensue as the ghost hunt unravels, but the key to Ghostwatch’s success is its cinema verite style and the deadpan performances, Parkinson in particular playing it straight as a ruler. Conversely, Craig Charles, who has never played it straight in his life, is the perfect foil; sceptical yet energetic, anything other than his trademark persona would have hampered the suspension of disbelief. Nevertheless, the moment that his fellow presenters drop their professional civility towards his mischief, we realise the stakes have been raised and the atmosphere that remains is truly chilling.

Ghostwatch’s infamous finale has become the stuff of TV legend, but in the interest of spoilers we will abstain from discussion, only noting that despite it being hard to pinpoint the exact genesis of Sir Michael Parkinson’s status as national treasure, having long been a serious journalist and acclaimed interviewer, this strange anomaly of TV programming may well be it. - Katie

Occult (2009) dir. Kōji Shiraishi

Oft touted as the baggier, more hangout-inflected cousin to Shiraishi’s laser-focussed bad vibe delivery system Noroi: The Curse (the best found footage horror not set in the Black Hills near Burkittsville, Maryland), Occult is a shoestring mockumentary about leech deities, portentous stones and, most chilling of all, people who like Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Beginning as a film about the victims of a mysterious knife attack, Shiraishi (playing a fictionalised version of himself) and his crew begin to spend time with one of the survivors, an affectless man who can charitably be described as bizarre and offputting. Taking pity on, or rather exploiting the man due to his lack of a home, the crew allow him to sleep in their production office in exchange for 24hr access to him as a documentary subject, hoping to capture some of the ‘miracles’ he claims he experiences as a result of the attack.

The turning point comes when the man casually intimates over some (many) drinks that he believes himself capable of traversing an interdimensional threshold by committing a large scale suicide bombing, which he is in the process of planning. Things spin out from there, with tentacular apparitions appearing over Tokyo, veteran horror director Kiyoshi Kurosawa arriving to dispense his inexplicable knowledge of Petroglyphic rock carvings, and the moral culpability of the crew being brought to the fore.

Shiraishi’s iconoclastic DV-cam diorama visual effects, often unfairly mischaracterised as cheap-looking, reject realism wholesale and bare their seams proudly. The resultant uncanniness is like pure cartoon collage logic hijacking the film, and it’s precisely this gung-ho embrace of the absurd that makes Occult such a joy. A circuitous DIY odyssey which builds to one of the most ludicrous go-for-broke endings in either horror or comedy, Occult is an untidy masterpiece, a deceptively silly film that also revels in excavating something dreadful out of mundanity. - Joe

Beyond Evil (1980) dir. Herb Freed

Picture, if you can, a uniquely nostalgic image: You’re a teenager in the early 2000s. It’s Friday night and a bunch of you are sleeping over at a friend’s house. You’re enjoying a banquet of the most opulent adolescent delights: Takeaway Pizza, Fangtastics and gallons of Coke that will either keep you up all night or surreptitiously line your sleeping bag with piss while you sleep. For boys, the order of business is generally PS2 games and airsofting each other in the butt. For girls, it’s dance choreography and prank calling other classmates.

But the centrepiece will be the bulky, grey CRT TV, which will remain on all night. At some deadly hour of the night, you flip through the only five channels and stumble upon an obscure horror film.

The era is unclear, but generally it’s late 70s to very early 90s. You’ll come in just too late to catch the title, and there’s absolutely no way you’ll ever find out what it was. There are no name-stars, no franchise ties, nothing to set any expectations. The performances are hammy, the dialogue laughable, the special effects cheap and nasty.

But, if you’re lucky, it’s no-fucks-given camp will give you a decent amount of shared laughs, and the approximation and appropriation of other, stronger horror films may even approach something of an atmosphere, even scaring the more sensitive members of your party into needing to go home.

Herb Freed’s Beyond Evil is one such film. Made in 1980, it draws influence from the B-movie tradition of the 50s, which itself was an outlet for trashy cash-cows which found new life in impressionable young film goers. Its plot is peak 70s capitalist horror story, a luxury, exotic property gets bought up by an upper-class couple but the curse upon it slowly drives them out. The closest thing it has to a star is post-Enter The Dragon John Saxon, decked out in silk shirts and chest-wig, one eyebrow permanently raised at all the spooky doings. It is derivative and drawn-out, committing far too much of its runtime to dramatic character building, like many low-rent horror of the 70s did.

But, in the hands of young, impressionable minds staying up far too late and peaking on a sugar high, it delivers the goods. It is a cheap but hearty laugh, committed performances of shitty writing, ineffective but earnest scares, budget effects work that is not immediately forgettable, and the whole thing is bolstered by a fairly formidable score by genre stalwart Pino Donaggio.

It would be a sad state of affairs to lose the accidental horror film experience to the streaming age. With the prevalence of on-demand viewing comes the loss of communal viewing, with audiences becoming very select about when and what they watch. But there’s something valuable about stumbling into a film that sets the bar so low, allowing a group of friends to retrofit the experience to their own needs. The mocking and laughter plants the seed for in-jokes and nostalgic storytelling that flourish many years after fact, and the experience lives on past the film’s sell-by date. - Tom