“ABRE LOS OJOS”: Spanish Horror and the Ethics of Looking

Imogen Radwan explores the dark world of Alejandro Amenábar’s 'Tesis' (1996), Franco’s Spain and the ethics of consuming violent media.

Since its prolific horror boom in the late 1960s to mid-70s, Spain has become something of an underdog in the production of gritty, visceral and terror-inducing cinema. From the early (s)exploitation films of the 60s/70s (99 Women, Las Vampiras), to the rise in found footage horror in the 00s (The REC franchise, Quarantine), to its own impressive catalogue of “haunted child” films (The Others, The Orphan) – each subgenre speaks to certain cultural and political anxieties that Spain has faced as the result of its turbulent recent history.

Since the 1970s, Spain has been woven into my own family tapestry in a way that has always led me to feel I’ve inherited some part of it, despite never having lived there, or being any part Spanish myself. My grandmother moved there from the UK in 1976, a point at which the country was making an unprecedented transition. At this moment in time, Spain was still a land decimated by one of the most brutal fascist regimes in history, its citizens recovering from the collective trauma of poverty, famine, war, and an almost total loss of democratic rights; in the same decade, the country’s southern coastline was being swiftly transformed into a hot, sangria-drenched playground for British tourists looking to escape the doom and gloom of their own increasingly authoritarian nation. Interestingly, the Spanish horror boom occurred at exactly the same time (writer Antonio Lázaro-Reboll cites this as taking place from 1968-75 in his book, Spanish Horror Film). From a sociopolitical perspective, it makes complete sense that a place which has been fed large doses of unimaginable horror in its recent history would find this percolating into its cinema. But rather than simply dwelling on the horror itself, this also makes Spanish filmmakers powerful commentators on the creation, dissemination and consumption of horrific images – and where the line between seeing evil and doing evil becomes blurred.

For example, when we browse the web, we each have an unconscious threshold for what we are willing to witness online. For many, this threshold often sits below content which is considered unconscionable to look at, despite our almost immediate access to it – most of which falls into the category of banned/illegal images and videos. Overriding any sense of morbid curiosity is often a strong aversion to partaking in the simple act of looking at material which could radically and detrimentally alter our view of others, ourselves, and the world. Drawing upon Laura Mulvey’s theory of scopophilic pleasure, such content forces us to adopt the “curious and controlling” gaze of the people that made it, thus eroding our empathic capacities towards the acts depicted, and rendering us complicit with them (Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema). But it’s hard to know where exactly we draw the line with what real-world pills we choose to swallow (see: our news cycle), and when it comes to the dissemination of “dangerous” media, nothing quite comments on it like Alejandro Amenábar’s 1996 film, Tesis (Thesis). Aptly titled, this dark and compelling adrenaline feast is also a rich visual thesis on what it means to be an active participant in the creation and consumption of horrifying media.

The opening to Amenábar’s film is as arresting as it is disturbing, and accurately sets the stage for the rest of the story. We open on Ángela, a young woman riding a subway carriage which has stopped due to someone jumping on the tracks. As Ángela disembarks the train, the conductor instructs the passengers: “Eyes off the track. There’s nothing to see.” While Angela does attempt to look over the platform’s edge, at the last moment she is pulled away by one of the station guards. This idea of active versus passive viewing sets a precedent which Ángela will spend the rest of the film grappling with, as a university student planning to write her thesis on audiovisual violence. Early on, she approaches a fellow student, Chema, stating, “I hear you like violent films, and you’ve got quite a collection.” It’s interesting the fearlessness with which Ángela poses this question; in the scene, it holds the almost humorous weight of a chat-up line, as if liking and collecting violent films is different to being violent – a distinction which the film constantly debates. As it happens, Chema holds a vast collection of gore, porn and snuff videos, which Ángela goes over to his apartment to watch, still not experiencing any clear sense of fear in his presence; after all, every film studies class has its Chema. In the ensuing drama, Ángela and Chema watch a stolen snuff video of Vanessa, a former student of their university who disappeared two years prior. From this point onwards, Ángela embarks on an investigation; not only of Vanessa’s murder, but of the ethics of what we choose to watch.

Within the first act of the film, there is a very telling monologue about the state of Spain’s cinema industry, spoken by a university professor, Castro:

“Our country has no cinema because there’s no concept of industry. No communication between the makers and their audience. We’ve reached a very critical stage; our cinema won’t be saved unless it is understood as an industrial phenomenon…there’s only one way to compete [with America]: give the public what it wants.”

In this speech, Castro delineates cinema as being a dialogue between a consumer (the audience) and an industrial supplier (the filmmaker). It’s painted as a fundamentally capitalist endeavour, a chain of supply and demand, no matter how bloody, gruesome or even vapid the content. While European auteurs lament the commercialisation of cinema – Tarkovsky described cinema as an “unhappy art as it depends on money” (A Poet in the Cinema, 1983) – Castro appears to be embracing the desublimation of this art form into a purely economic activity. In a country which has been characterised by scarcity until the 1980s, you can feel this desperation in his choice of language (“has no…there’s no…critical stage…won’t be saved unless…only one way).

The conclusion then, is that if the public wants violence, the public gets violence. But whereas America’s violent media is often highly staged, and filtered through a trained understanding of what exactly the public can stomach – even at the level of the news cycle – Spain has an ultimately different background, which gives Spanish horror a qualitative edge over mainstream American horror. The latter tends to be grounded in a sense of unreality – an explosion of our deepest fears, reimagined for the screen in a way that provides a sense of blood-tingling escapism. The former, however, is grounded in a reality of true, inherited political trauma, even if the filmmakers didn’t experience it directly. One example of this is Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia’s 2019 film El Hoyo (The Platform), an allegorical horror based on the premise that in a 300+ storey tower, a slowly descending platform of food should make its way to the lowest floor with enough to spare for everyone, should the residents on the floors above it not over-eat. As you can imagine, it’s not far below the 100th floor that cannibalism starts to take hold. With Spain’s notorious history of starvation under Franco’s regime, a film which uses cannibalism as the only response to this system of entrapment in such a visceral and terrifying way, descends to the core of one’s collective historical trauma. Guillermo del Toro’s dark fairytale, Pan’s Labyrinth (actually Mexican but set in Franco’s Spain), is also a prime example of how even the most fantastical films within this genre are still grounded in a horror which is not conceptual, but tangible.

So what does this have to do with the ethics of looking at, seeing and enjoying horrifying media, which is so heavily debated in Tesis? To return to why so many of us could never stomach a real snuff film without needing therapy – but will sleep soundly on a fictional torture scene – this is because we see a clear ethical line dividing how these images were produced. But in a nation where real, lived horror precedes a commercial boom in fictional horror, a snuff tape might just be the cultural cliff edge – the apotheosis in the whole debate of the ethics of visual consumption.

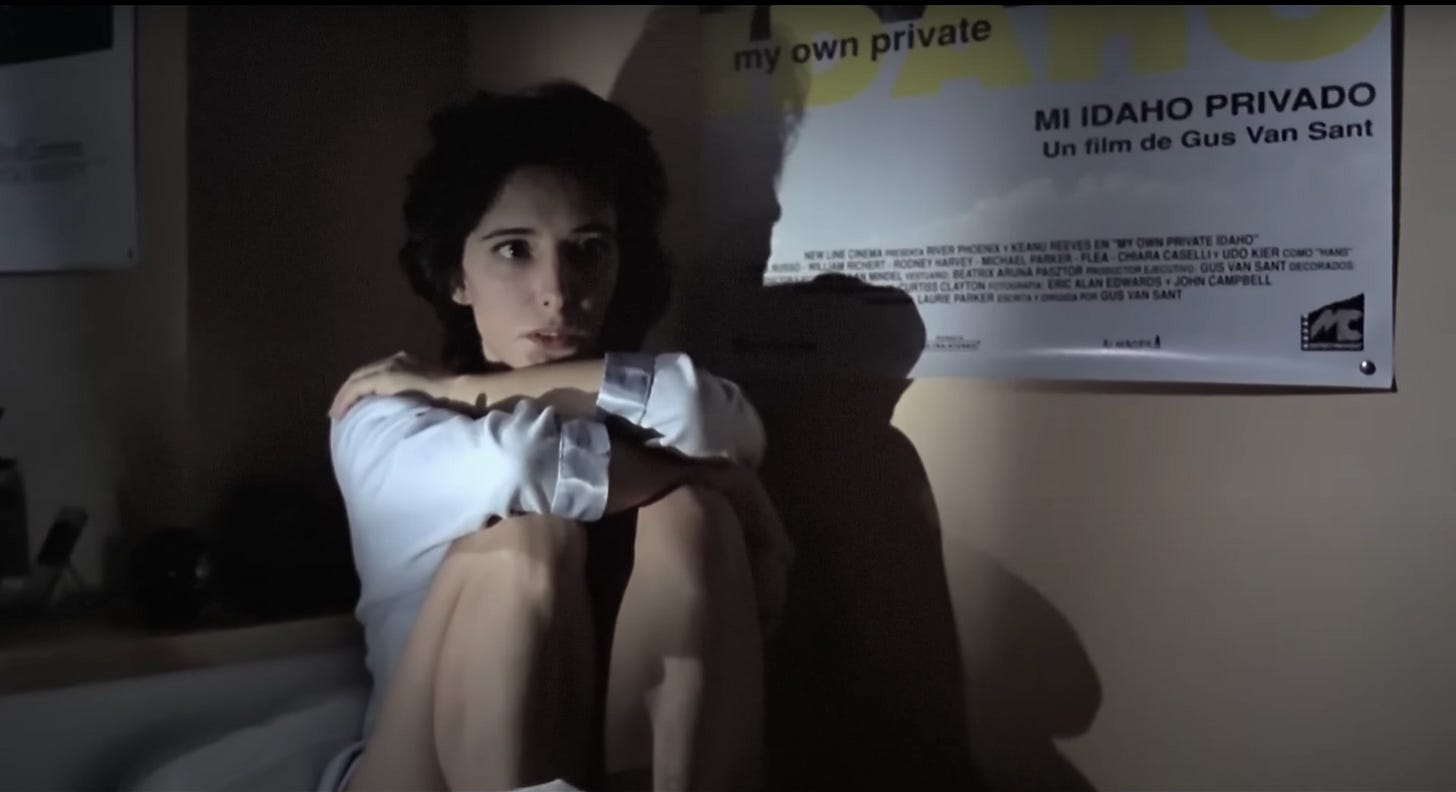

You may notice that Spanish horror and thriller films have a strange preoccupation with the eyes and seeing; Amenábar’s breakout film is entitled Abre los ojos (Open Your Eyes, 1997); REC (2007) follows a young woman with a camcorder around an enclosed apartment block, tracking her perspective within a claustrophobic space; and of course, the Pale Man in Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) is a monster with empty eye sockets, his eyeballs embedded in his palms. To return to Tesis, above Ángela’s bed is a prominent poster for the 1992 film My Own Private Idaho, a road movie about two men on a journey of personal discovery. If we break this down, we may also read My Own Private Eye(daho). If Ángela is the private eye of her own narrative, what kind of truth about herself is she discovering? Central to Tesis is the lingering question: What do our viewing choices implicate within ourselves? In the film’s many attempts to answer such a question, we are only propelled further into ambiguity.

At its core, the terrifying quality of Spanish horror lies in its unflinching engagement with real, human evil, in a way that has been scrupulously packaged for a commercial audience. And while the privileged may choose to avert their gaze from the most horrific truths of our civilisation, those who have suffered the most cannot. Spanish horror tends to undermine itself by posing as something far more sensationalist than it actually is; on closer inspection, many of these films are imploring us to do something that no commercial filmmaker ever would – an invitation resonating with the very act of seeing: Abre los ojos.

Written by Imogen Radwan.

Enjoy the darker side of cinema? Make sure you’re following her new programming initiative, Violet Hour Cinema, for access to all things macabre, unsettling and transgressive.